Tadeusz Bieńkowicz was a member of the resistance and took part in one of the largest actions to free prisoners in occupied Poland. Tadeusz fought against the German occupation and later also against the Communist regime.

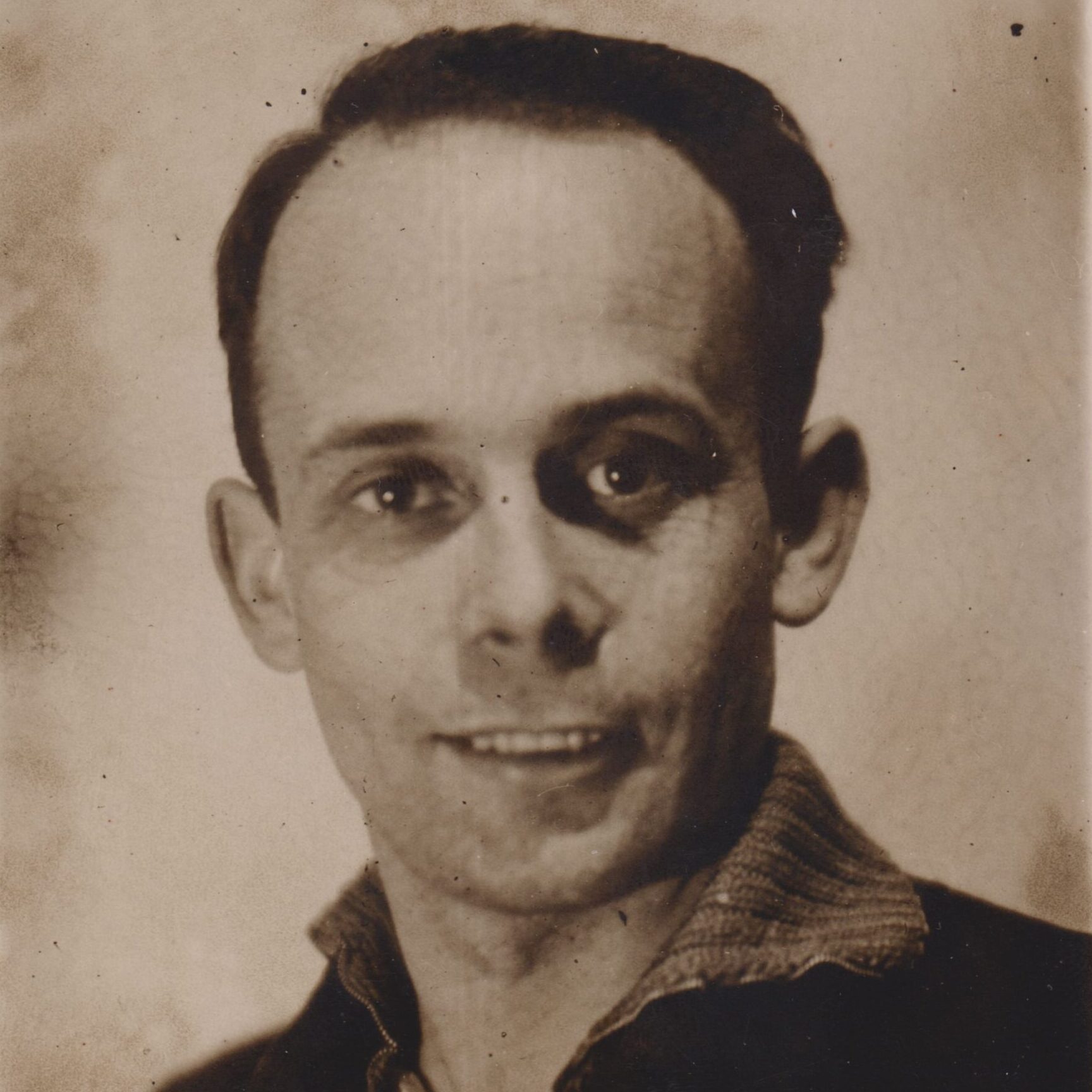

Tadeusz Bieńkowicz was born on 19 April 1923 in Lida. When the Second World War began he volunteered for service and was given a job at an air observation post. When the Soviet occupation began, he joined the resistance movement and in 1943 he became a soldier in the Home Army.

He became a soldier of diversion unit which attacked German strategic infrastructure. He was promoted to platoon commander in the 2nd Battalion of the 77th Infantry Regiment of the Home Army. Tadeusz fought in the eastern borderlands of Poland, where the Polish resistance movement fought both against the German forces, as well as against the communists.

In the autumn of 1943, the intelligence of the Home Army learned that about 70 members of the resistance were being held in the prison in Lida. The commanders decided to capture the prison and free the detainees. At that time, Lida was an important transport hub for the German forces. There was a garrison of about 10,000 German soldiers and policemen in the city, making this a very risky operation.

The commanders of the Home Army in this area ordered a small detachment of the best-trained soldiers to disguise themselves. These men managed to trick the guards and succeeded in capturing the prison. The action took place on the night of 18/19 January 1944. Resistance members were freed, leaving criminal prisoners.

During the action, Home Army soldiers discovered that among the prison staff there was a Russian wanted by the resistance movement for crimes he had committed against the local civilian population. Tadeusz Bieńkowicz killed the person in question for his crimes.

The action was successful. The people were freed without firing a shot. The German city garrison was not warned and did not react. Tadeusz Bieńkowicz was decorated with the Virtuti Militari, Poland’s highest military decoration for this action.

Tadeusz Bieńkowicz remained a member of the resistance after the war. He decided to fight against the communist regime. He was arrested in 1950 and after a few years he was released from prison.

In the 1990’s Tadeusz was rehabilitated by the Polish government and in 2018 the was promoted to honorary general. Tadeusz passed away on 13 December 2019.