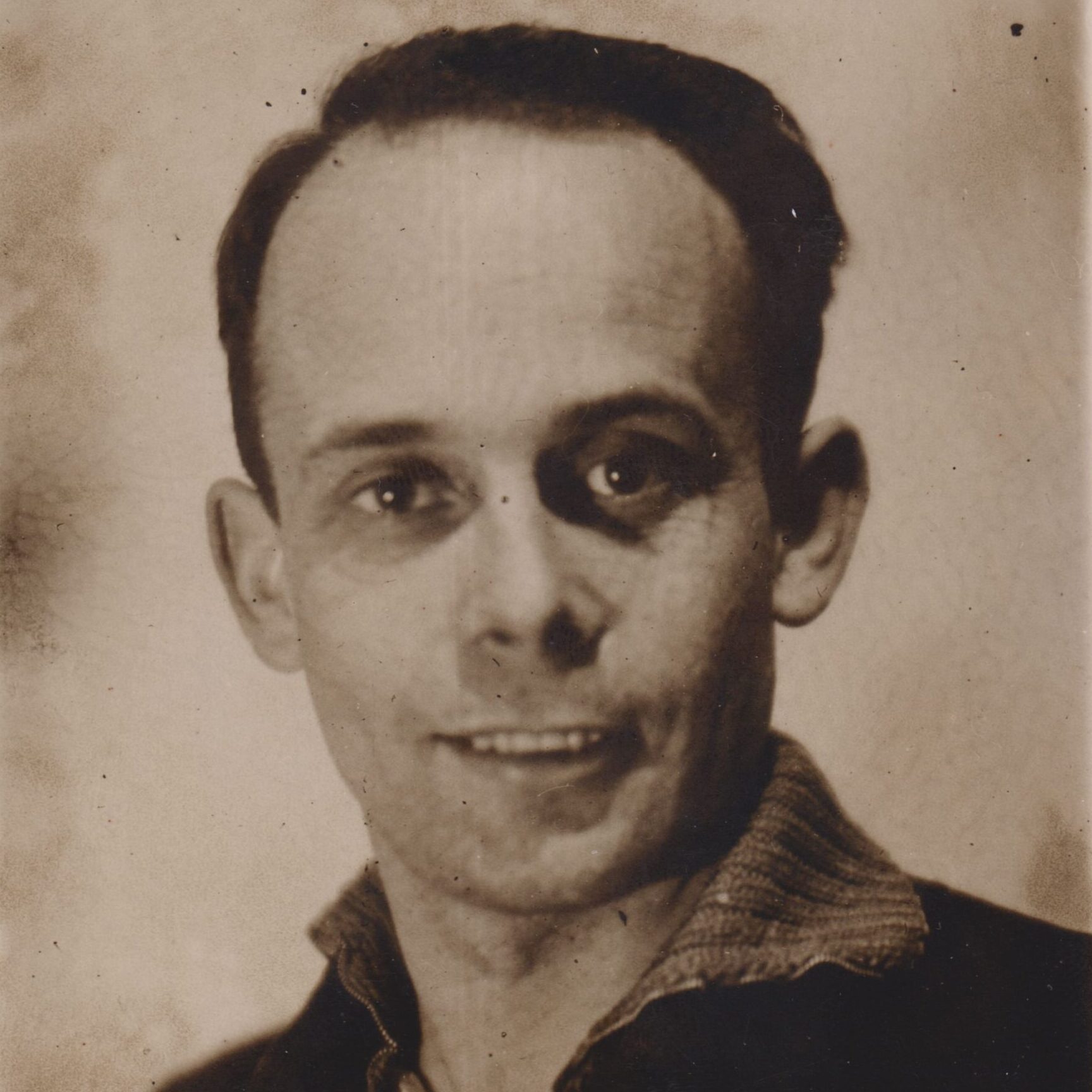

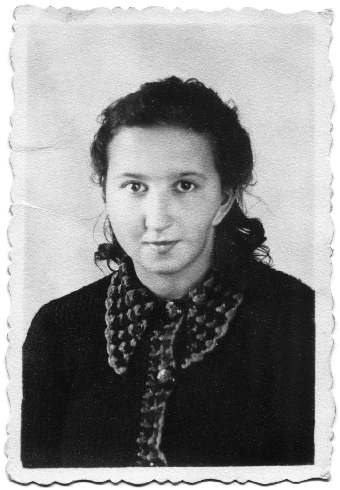

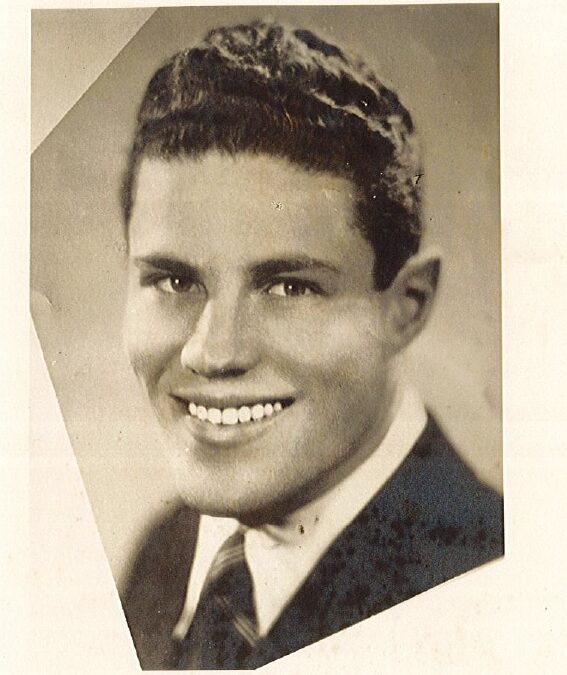

Zenon Malik was a Polish soldier and officer. During the occupation of Poland he joined the Home Army in Kraków and gathered intelligence for the resistance.

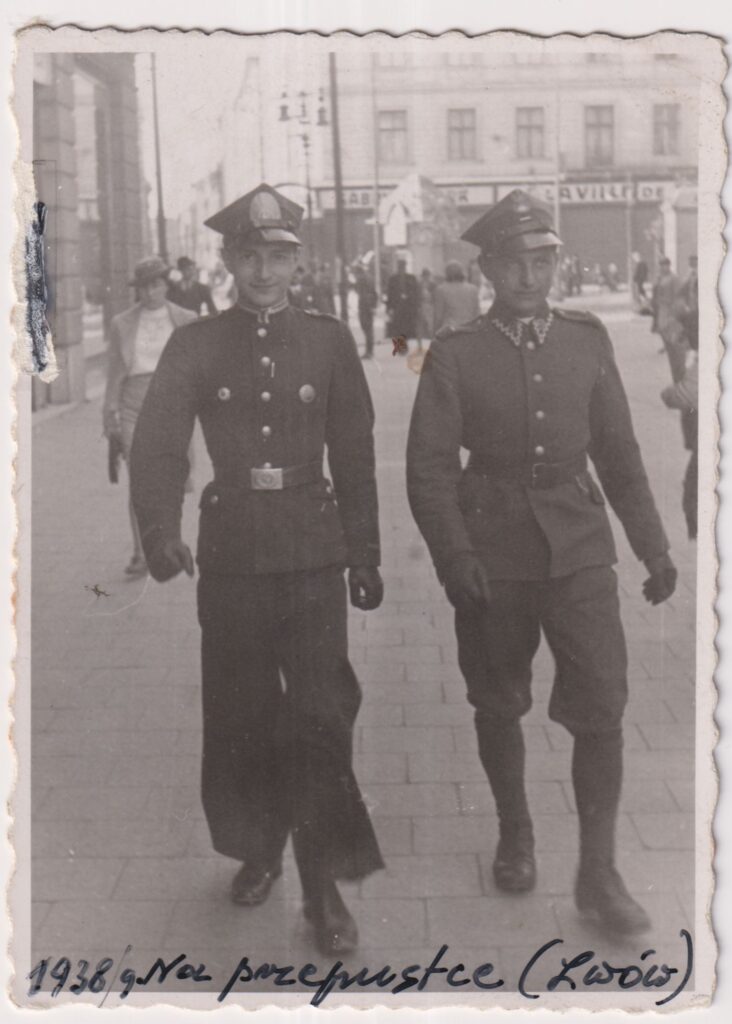

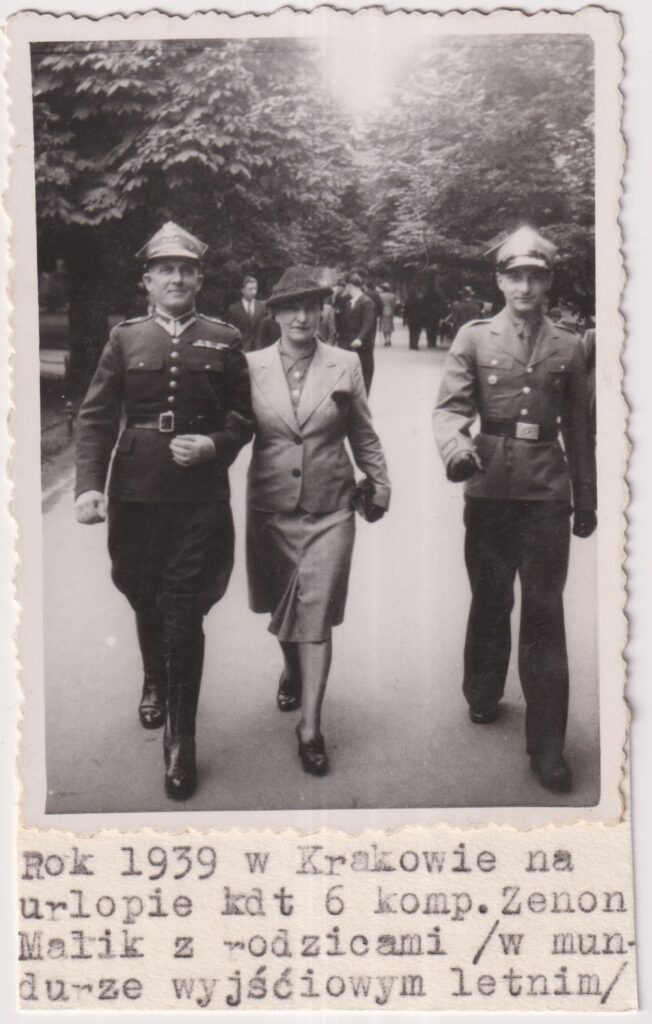

Zenon Malik was born in Kraków on 18 August 1920. He was a cadet of the Lviv Cadet Corps No. 1. J. Piłsudski. Zenon participated in the defense campaign in 1939 as a messenger in the 20th Infantry Regiment of the Polish Army.

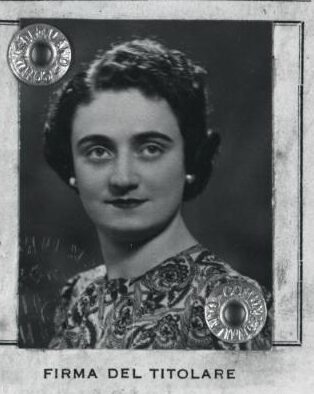

He joined the resistance right after the occupation began in 1939. He took part in a non-commissioned officer course. He served in diversion and sabotage, and conducted non-commissioned officer courses for other resistance members in Kraków before becoming an intelligence officer.

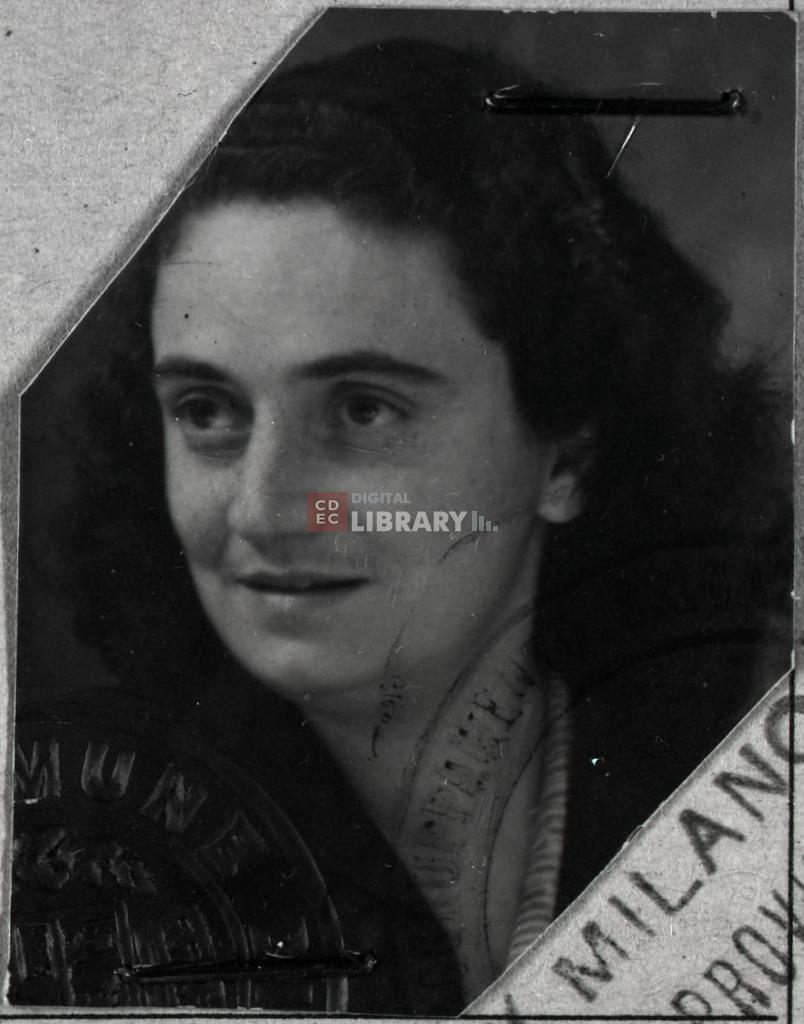

Zenon was forced to join the German Baudienst (construction service) in 1941. He was then transferred to work in the Military Hospital at Copernicus street and in 1943 at the Bacteriological Institute at Pure street. Zenon worked as a lice feeder and cleaner. The lice were used for research into typhus vaccines. These jobs allowed him to gather intelligence.

Zenon spoke German and he talked to Wehrmacht soldiers about the situation on the eastern front. He managed to gain their trust and befriended them, which allowed him to obtain a lot of valuable information about the situation of the German army at the front.

Zenon received information that the German forces were on to him and had to flee Kraków in 1944. He spent the rest of the war in hiding in Brzesko.

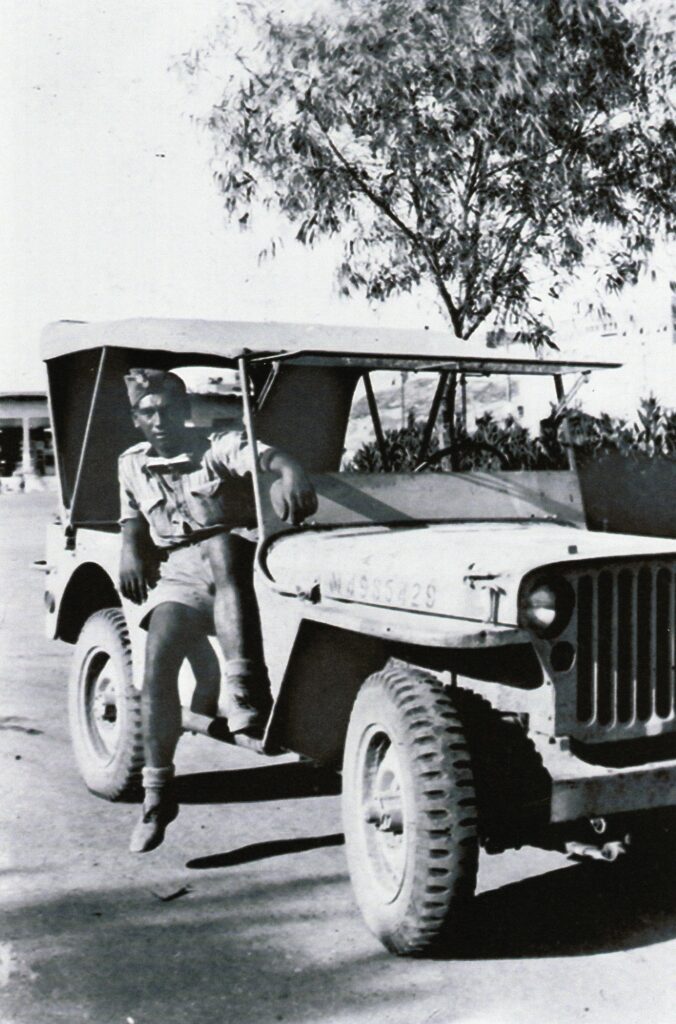

After the war Zenon was harassed by the communist regime. After 1990, he was among the founders of the World Association of Home Army Soldiers and then of the Independent World Association of Home Army Soldiers. He was a co-founder of the Museum of the History of the Home Army, which turned into the current Home Army Museum.

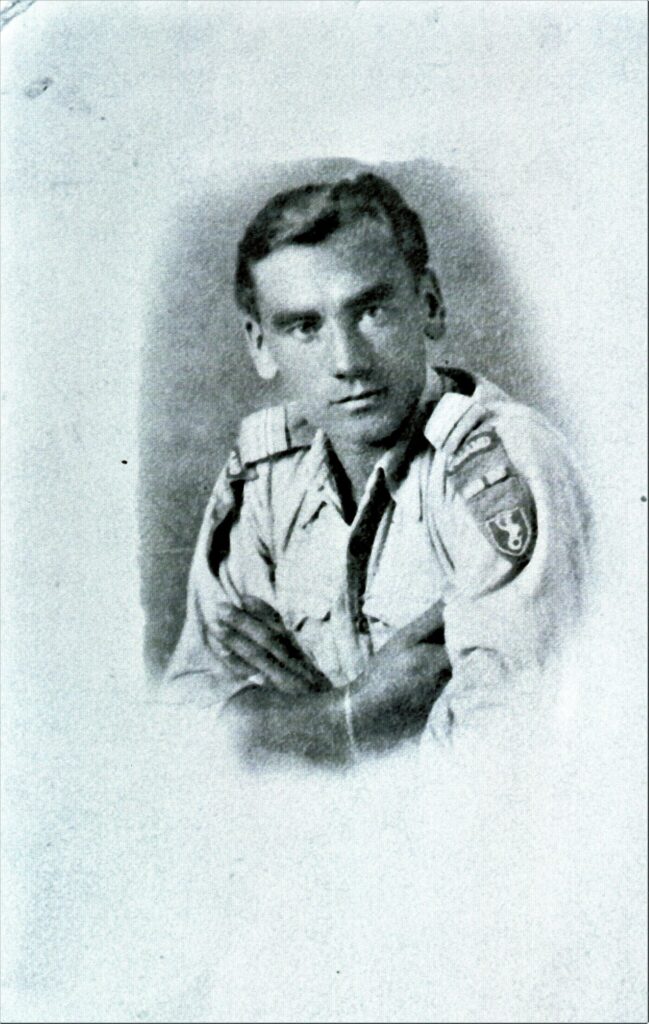

Zenon was decorated with the Bronze Cross of Merit with Swords, the Home Army Cross, and the Army Medal for War 1939-45. He passed away on 3 April 2018.

© Home Army Museum