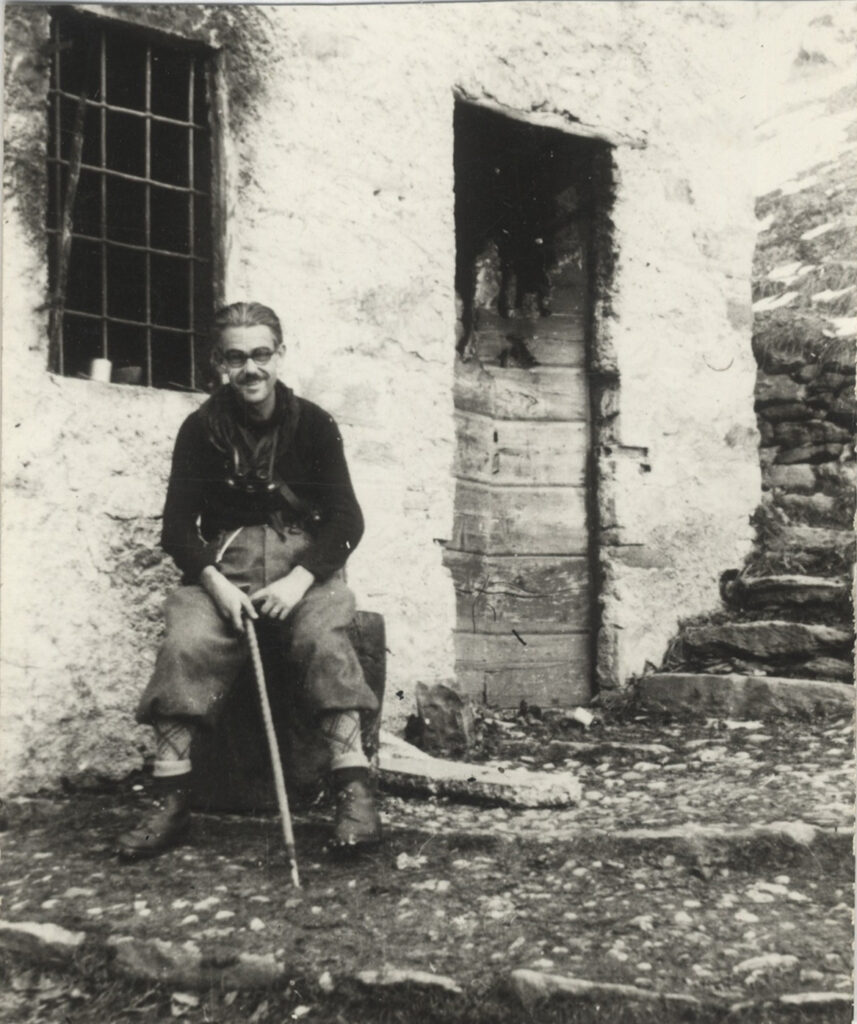

Carlo Travaglini was German on his mother’s side, and was an independent partisan who managed to save numerous Italian soldiers through his skills as a forger.

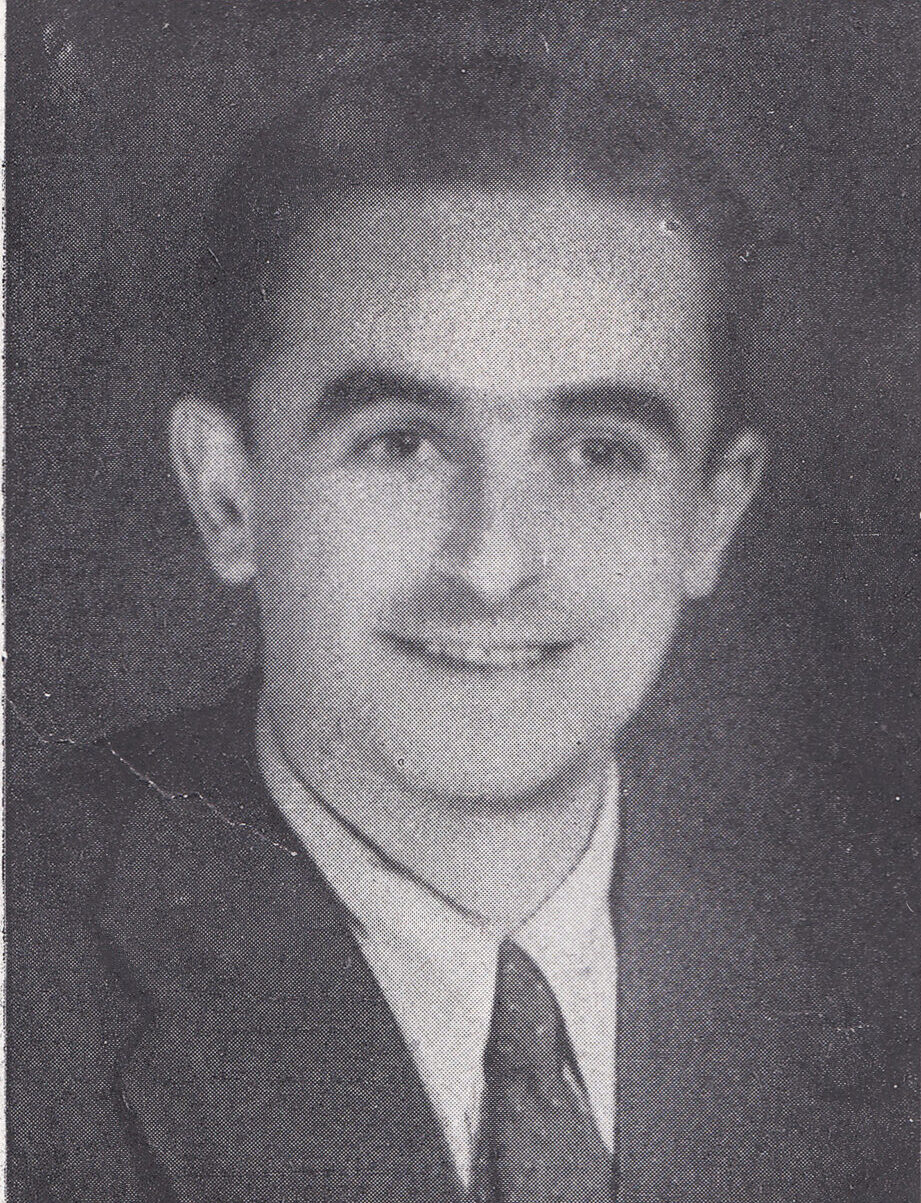

Carlo Travaglini was born in Dortmund in November 1905 where his father was serving as a conductor of a military symphony orchestra. Carlo left the family at the age of eighteen and worked various jobs to maintain himself while studying literature at university.

In 1935 Carlo ran into trouble with the Nazi regime after he wrote a novel in which he stated that “a poor honest Jew is worth exactly as much as a poor honest Christian”. Carlo was arrested in 1936 and sentenced to four months in a concentration camp by a special tribunal. After serving his sentence he was expelled from the Reich as an “unwanted foreigner”. He then moved to Italy where he had to fulfil his military service obligations and was assigned to the Alpini corps.

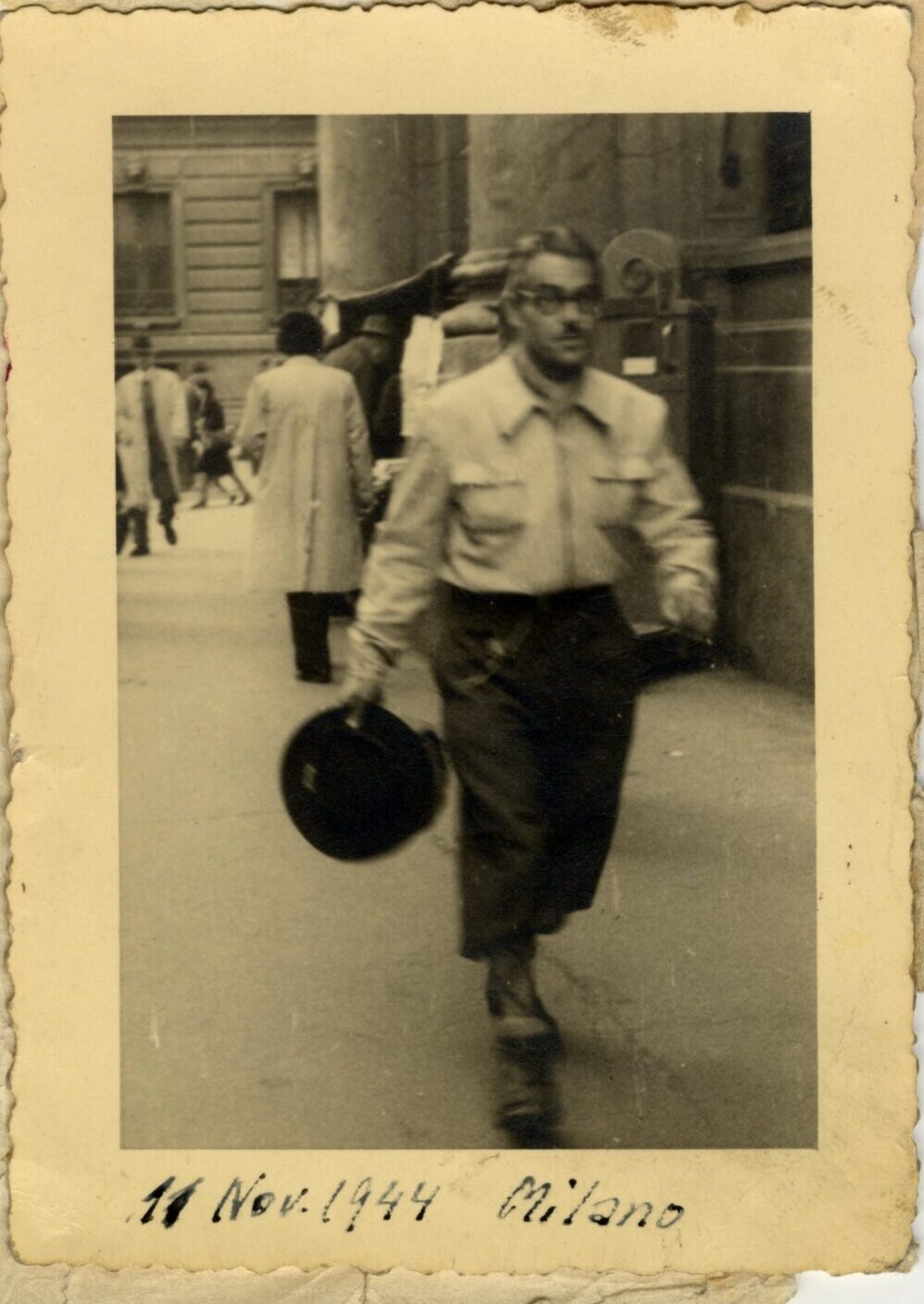

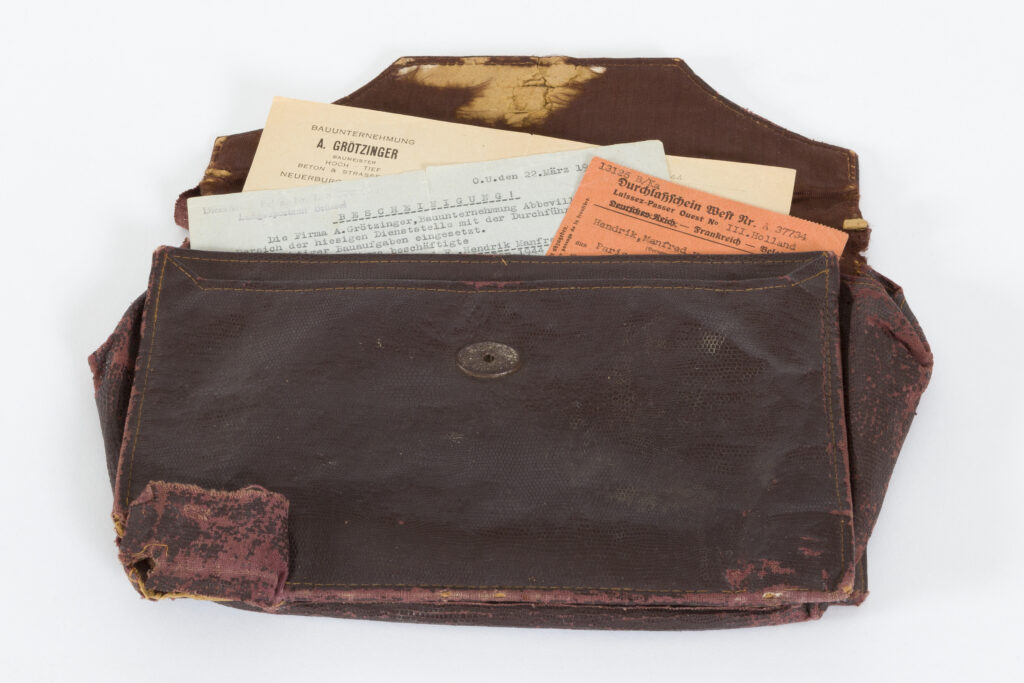

Eventually Carlo found a job as a technician in the Magneti Marelli factory in Milan. After the German occupation of northern Italy on 8 September 1943, the fate of the scattered Italian military soldiers was dramatic and hundreds of thousands were deported to Germany. One day Carlo noticed some women in front of the Hotel Titanus which was occupied by the Nazi command looking for news about their husbands. Carlo passed himself off as a German and entered the hotel to ask the Nazi soldiers for information. From this moment on, Travaglini displayed incredible skills as a forger and showed an uncommon ability to deceive people.

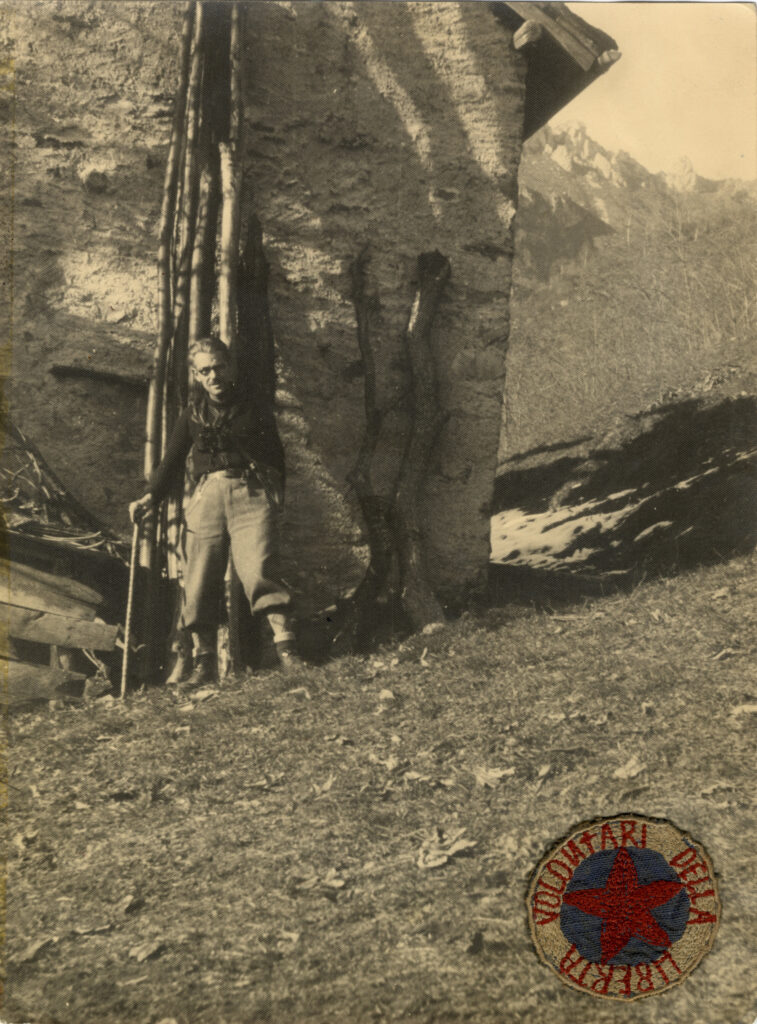

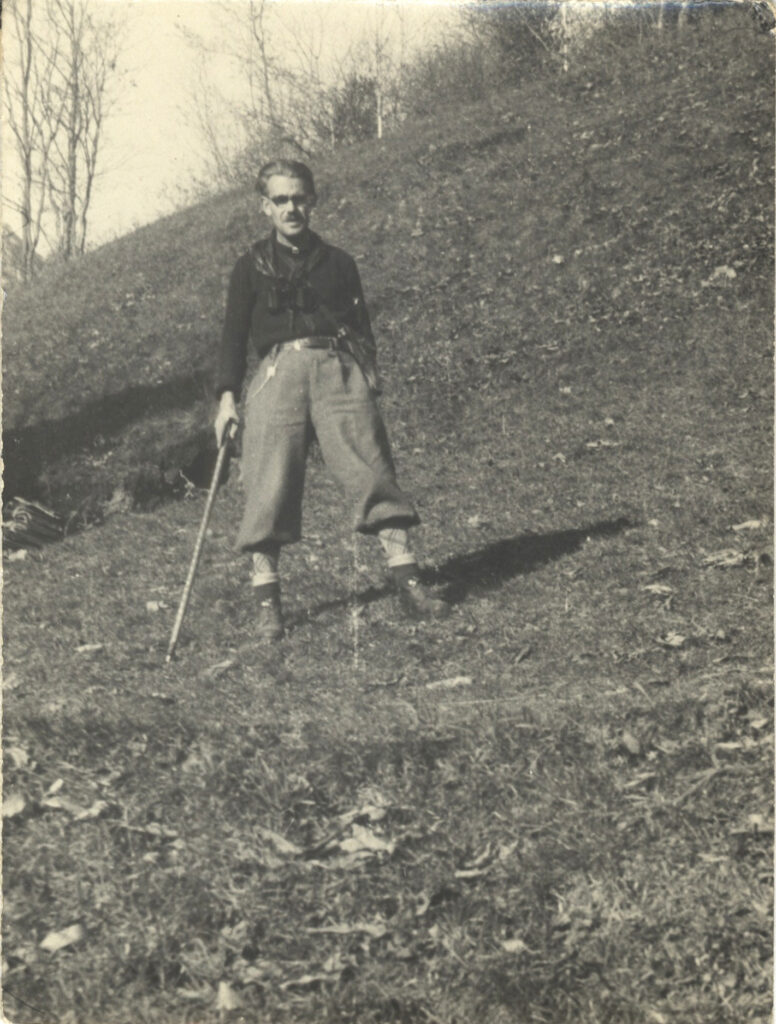

Travaglini managed to convince the Nazis that it was better to have soldiers work in Italian factories instead of deporting them and created fake demands from the factories for manpower. Thanks to this risky activity, he was able to save many soldiers from deportation and bring back many more. Travagliani also stole stamps and produced false documents to support his activities and to allow Jews and Allied pilots to flee to Switzerland. On 30 June 1944, he was discovered by the Nazis but he managed to escape. He was sentenced to death but luckily he was never caught. Carlo joined the 89th Garibaldi Alpi Grigne Brigade with whom he served until the end of the war.