Out of a great sense of justice, red-haired Jo Schaft went to study law in Amsterdam in 1938. During the occupation, Jo helped oppressed people. Her pseudonym in the resistance was: Hannie. Under that name she later became famous.

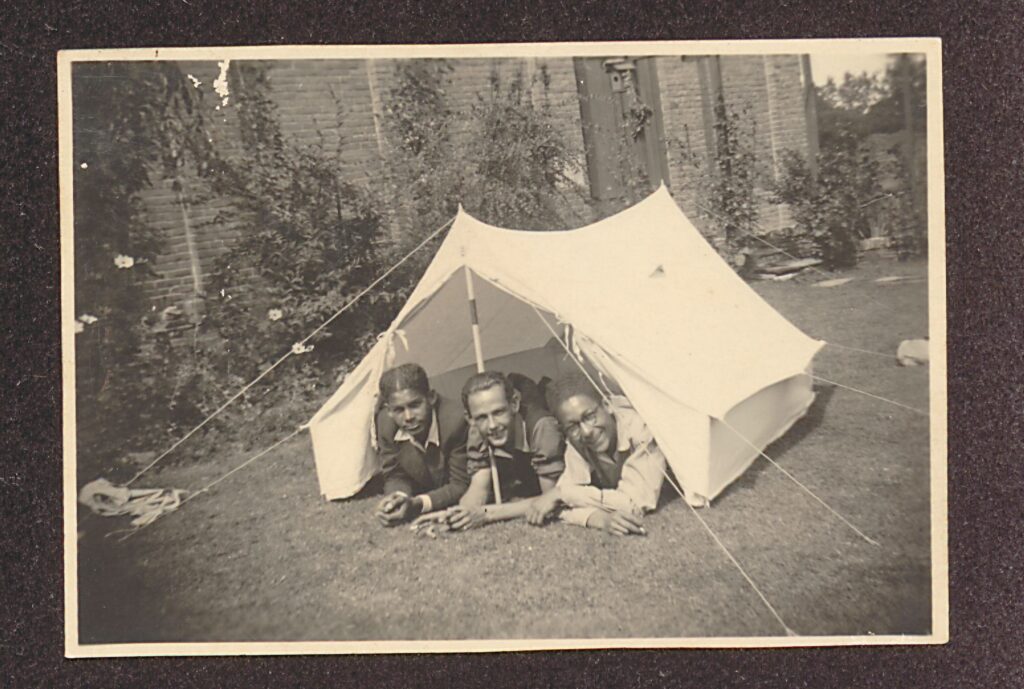

At the beginning of the war, life seemed to go on as usual. Hannie studied and spent a lot of time with her fellow students and friends Sonja Frenk and Philine Polak, who were Jewish. From the autumn of 1940, her friends faced anti-Jewish measures which made Hannie furious. When Sonja and Philine had to wear a Star of David, Hannie decided to steal personal identity cards for them from people who were not Jewish. It was her first act of resistance. Later she stole many more identity cards and arranged hiding addresses.

In early 1943, every student in the Netherlands had to sign a ‘declaration of loyalty’, promising that they would obey the occupying forces. Those who refused were no longer allowed to study. Hannie did not sign and devoted herself entirely to the resistance. She then chose the most extreme form of resistance: she joined a group of communist resistance fighters who carried out assassinations of collaborators.

Hannie often carried out her missions together with her resistance friend Truus Oversteegen. “I had disguised myself as a man so that Hannie and I could pretend to be a couple in love”, Truus explained. “Shooting traitors was a terrible thing. But it had to be done. After all, we couldn’t put them in prison.”

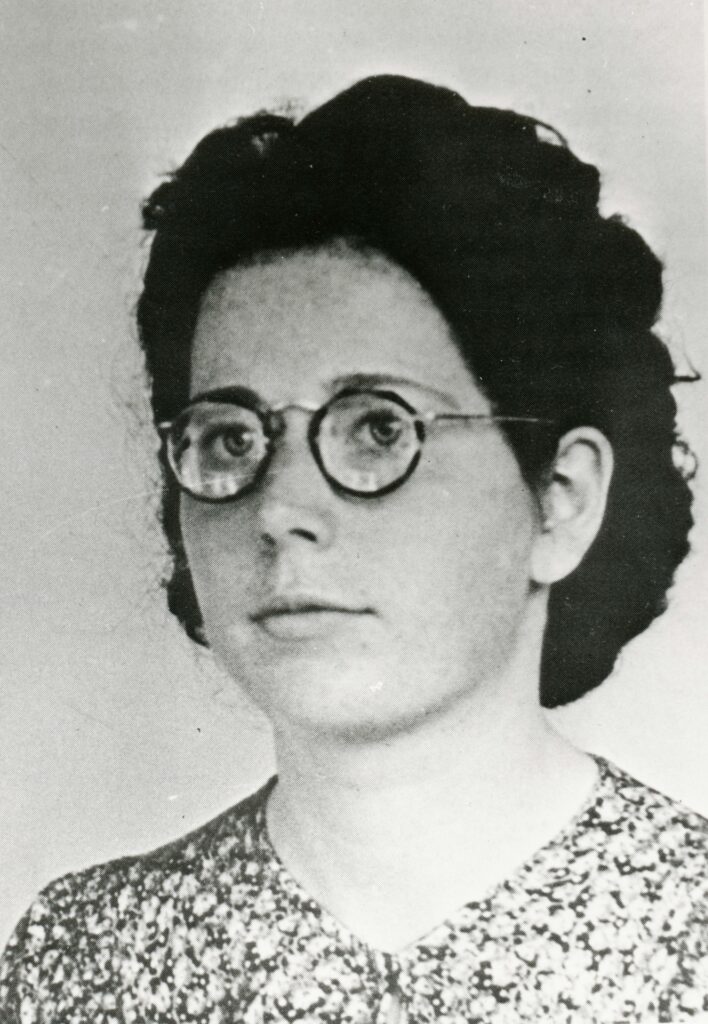

After learning that the German forces were looking for a red-haired girl, Hannie dyed her hair black and began wearing eyeglasses. But one day, in March 1945, she was stopped at a checkpoint on the street and found to be carrying illegal newspapers and a gun. She was recognised as ‘the girl with the red hair’. After being interrogated for days and nights on end, Hannie admitted to her part in the resistance, but she did not mention any names. On 17 April, three weeks before the Netherlands was liberated, she was taken to the dunes and was shot without a trial. She was 24 years old.

© Beeldbank WO2 – NIOD