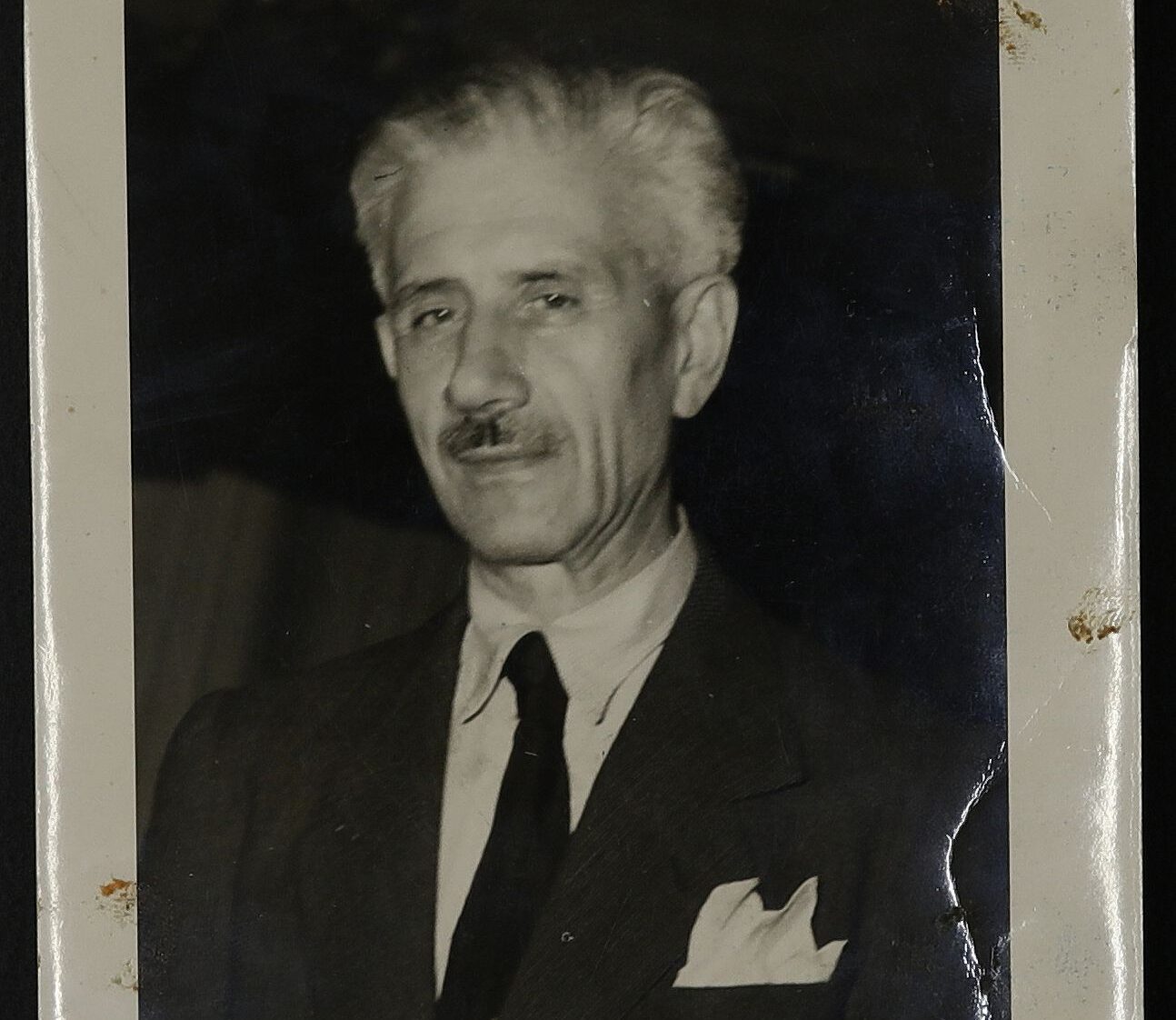

Alfredo Malgeri was the commander of the Guardia di Finanza (Financial Guard) in Milan. He played an important role in the Italian resistance movement and the liberation of Milan.

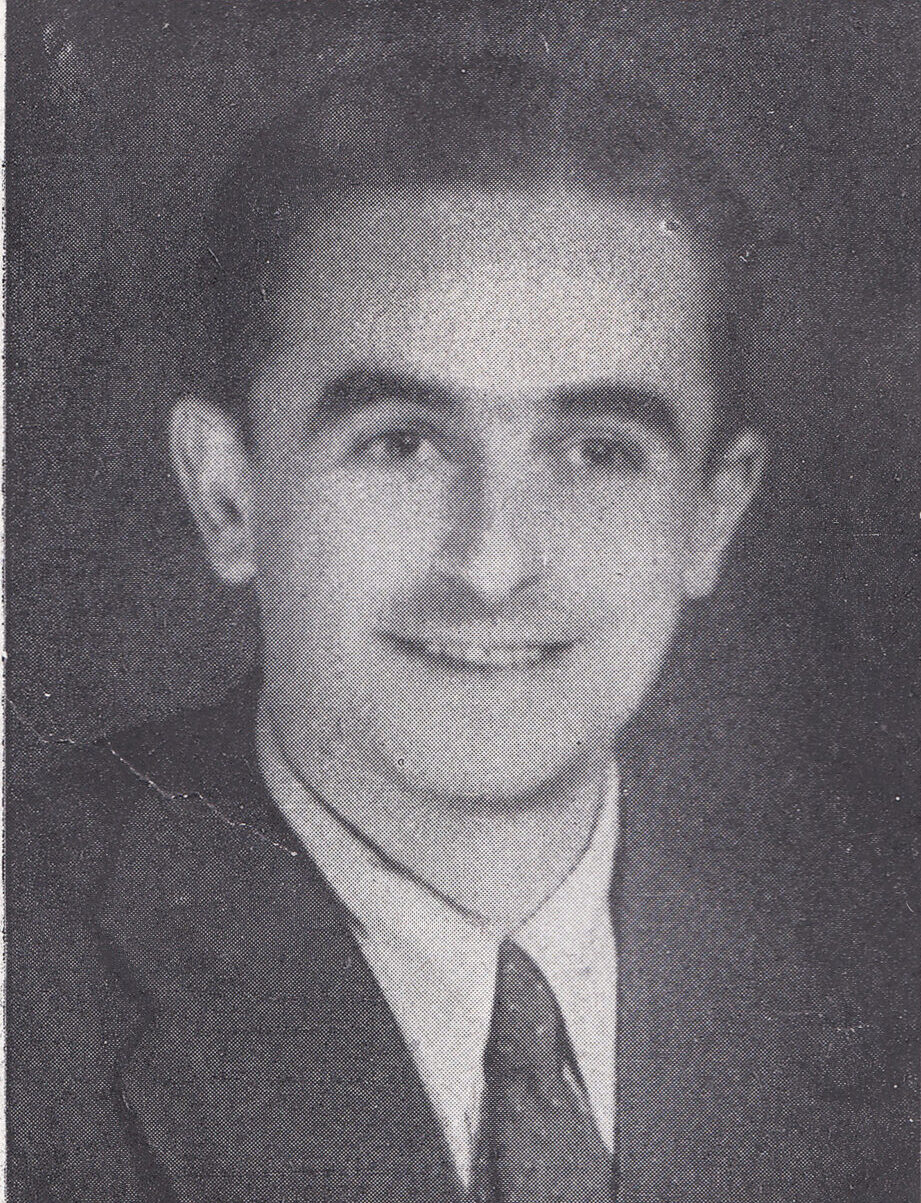

Alfredo Malgeri was born in Reggio Calabria on 14 August 1892. In 1912 joined the Guardia di Finanza (Financial Guard). He had a successful career with many prestigious jobs around Italy.

In July 1942 Malgeri was assigned as commander of the Guardia di Finanza in Milan. After the Nazis occupied northern Italy the Guardia di Finanza was not disbanded like the other armed forces of the Italian government and Malgeri and his men remained in Milan.

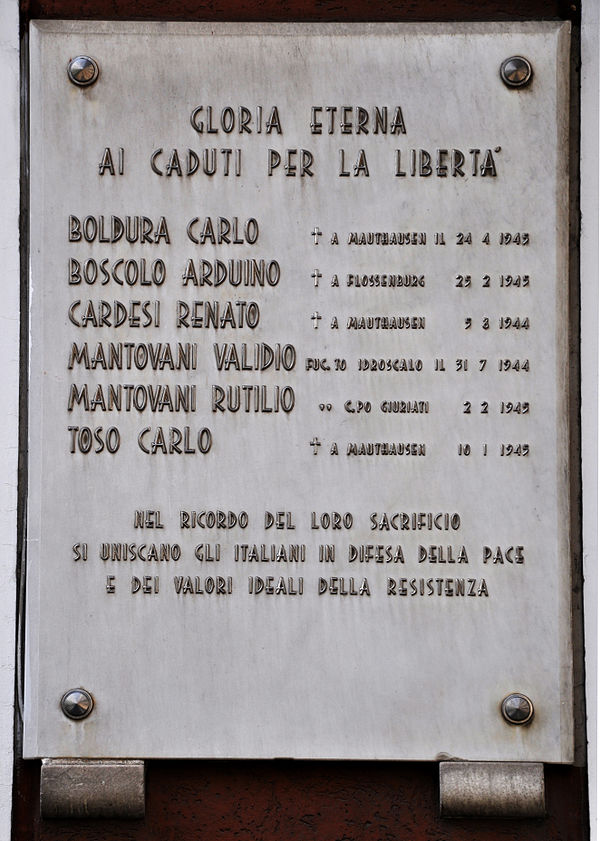

Malgeri managed to secretly make contacts with partisan commands and the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale Alta Italia (National Liberation Committee of Upper Italy) and decided to help them. Under the command of Malgeri the Guardia di Finanza helped Italian and Allied soldiers who had escaped from prison camps and also allowed Jews to cross the border into Switzerland when they could. The organisation also protected partisans and Jews against round-ups and persecution. Malgeri would also organise fake actions against partisan bands in which he did not attack them but instead brought the money, weapons and information.

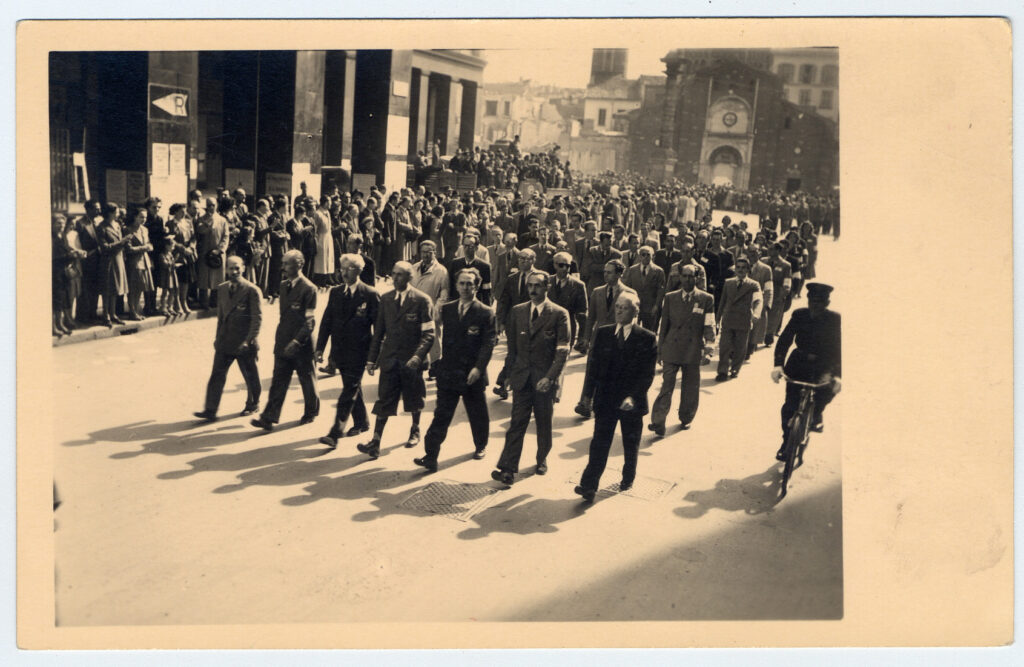

In April 1945, Malgeri made arrangements with general Raffaele Cadorna of the Corpo Volontari della Libertà (Freedom Volunteer Corps) to support the partisans in a general insurrection. The Guardia di Finanza numbered less than 450 soldiers against an estimated presence of tens of thousands armed fascists.

The local resistance leadership in Milan ordered Malgeri to take possession of the Prefecture of Milan and to seize several other important buildings and factories throughout the city. Malgeri and his men left their barracks to carry out the order. At 06:00 on 26 April, the Prefecture was taken over and at 08:00 Malgeri sounded the air-raid alarm three times to give the signal that Milan had been liberated.

In 2007, Malgeri was posthumously awarded the Gold Medal for Valour of the Guardia di Finanza with the following motivation: “In an extremely difficult political-military situation […] he decisively and at great personal risk opposed the republican fascist government’s intentions to use the Guardia di Finanza against the clandestine expatriation of Jews and persecuted persons and in anti-guerrilla operations against the Resistance”.