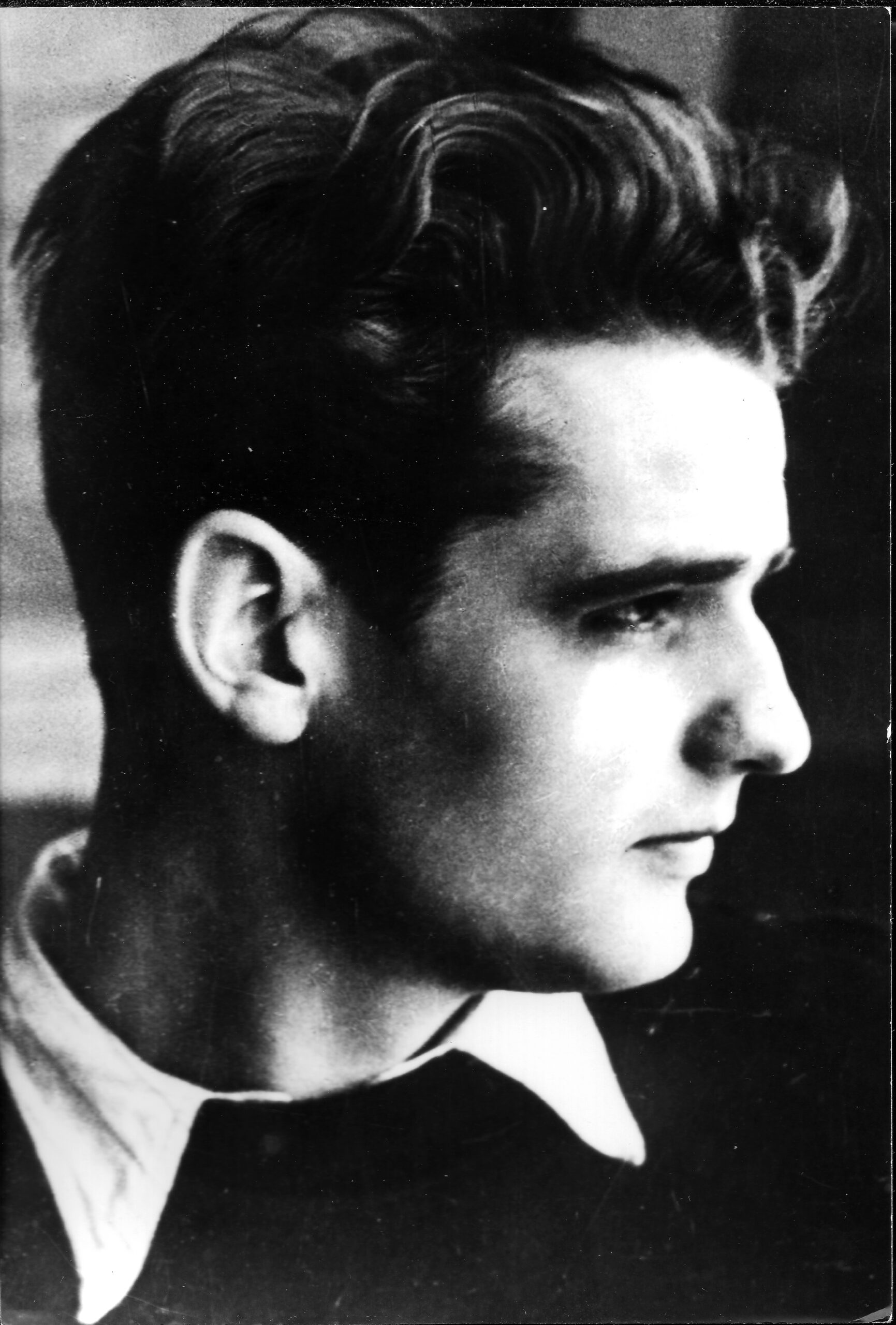

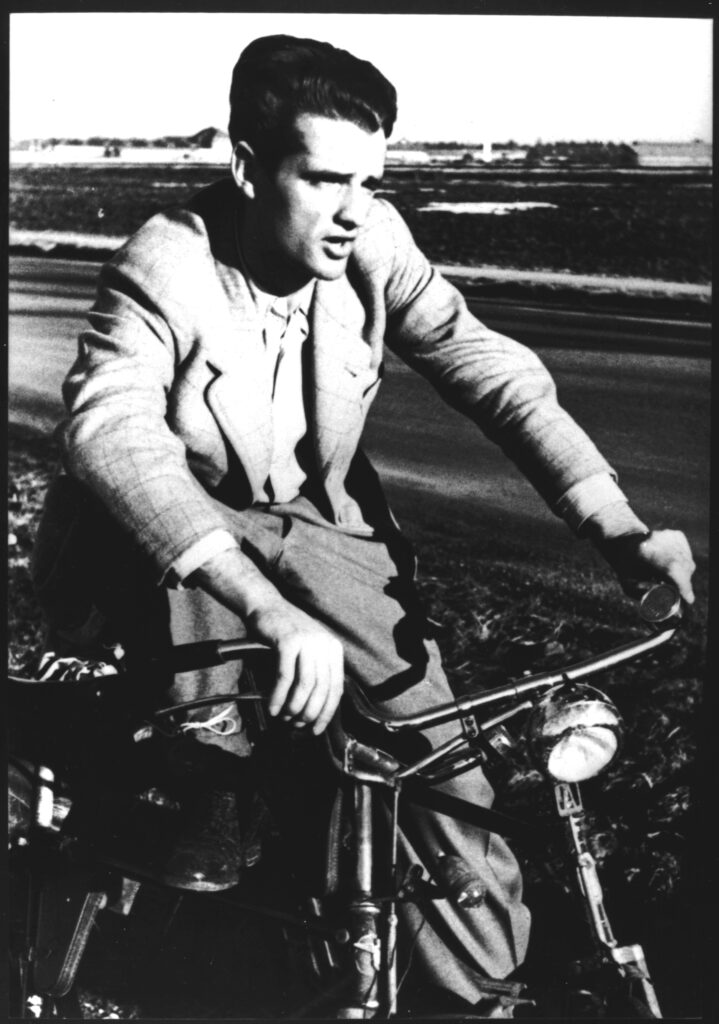

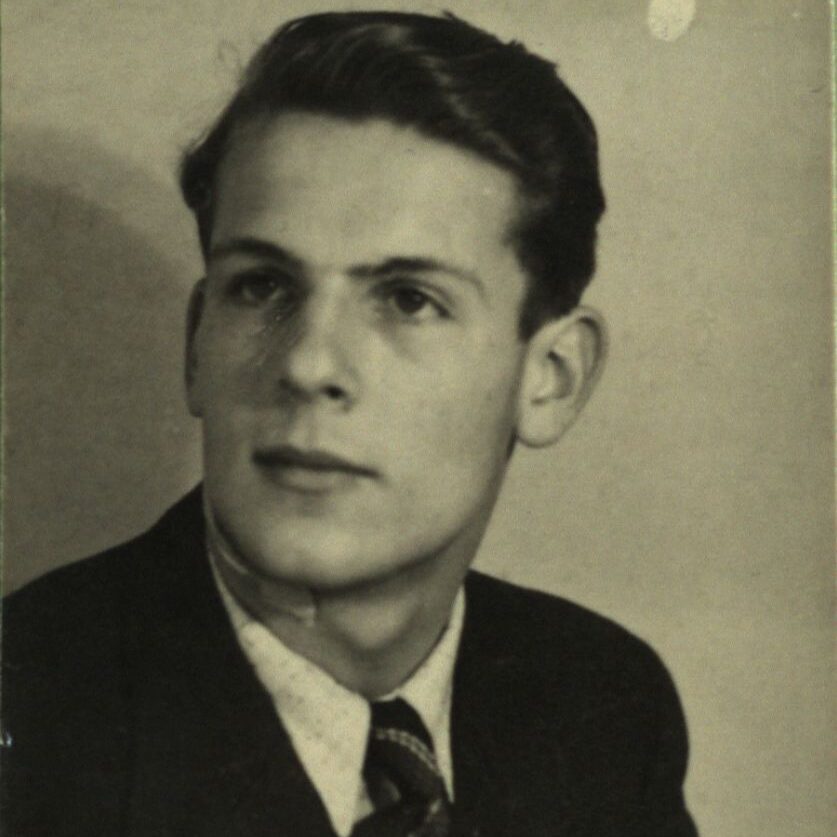

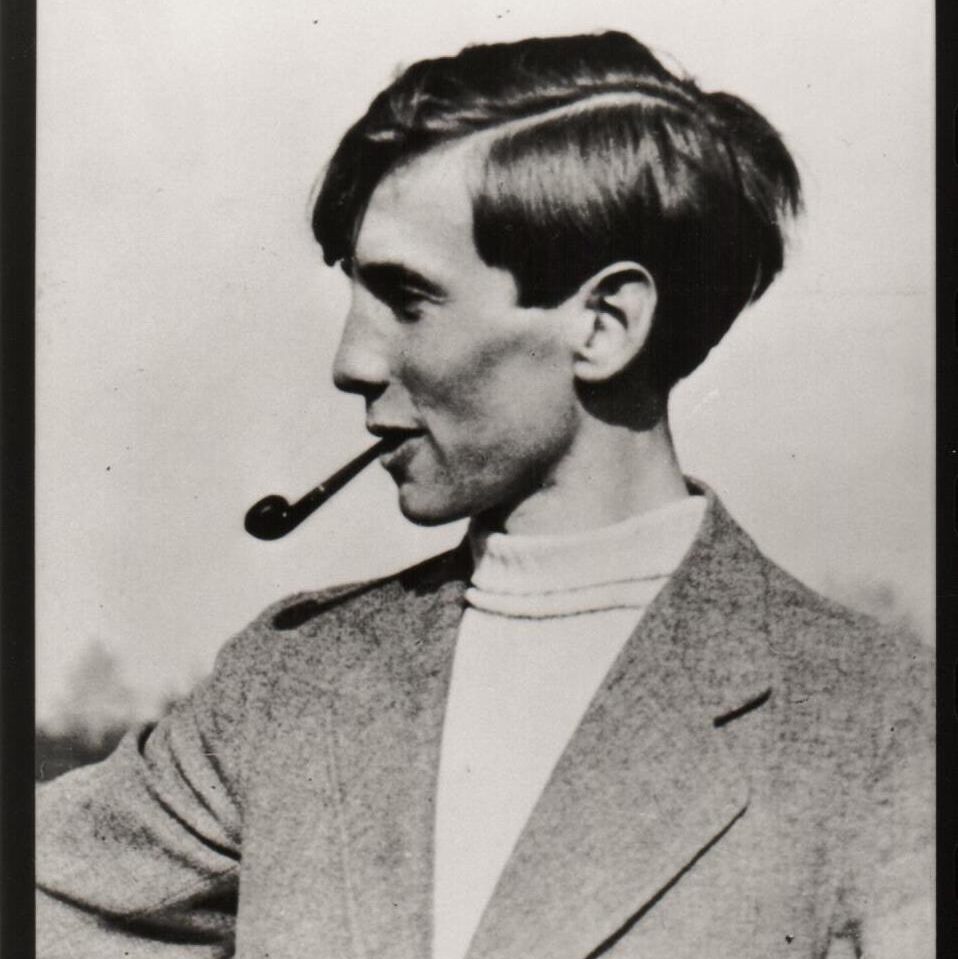

Willi Graf was an devout Catholic and an active supporter of the White Rose. He was forced to serve as a medical orderly for almost two years and was shocked by the atrocities he witnessed, in Poland and especially in the Soviet Union. In vain he tried to convince friends to join the resistance.

Willi Graf was born in 1918 in the Rhineland and moved to Saarbrücken with his family in 1922. At the age of eleven, Graf joined a reform-oriented Catholic youth association, from 1934 on he also took part in a Catholic boys’ association called Grauer Orden, even when it was banned in 1936. In January 1938 he was imprisoned for some weeks because of his involvement with the Catholic youth organization. Willi Graf constantly refused to join the Hitler Youth.

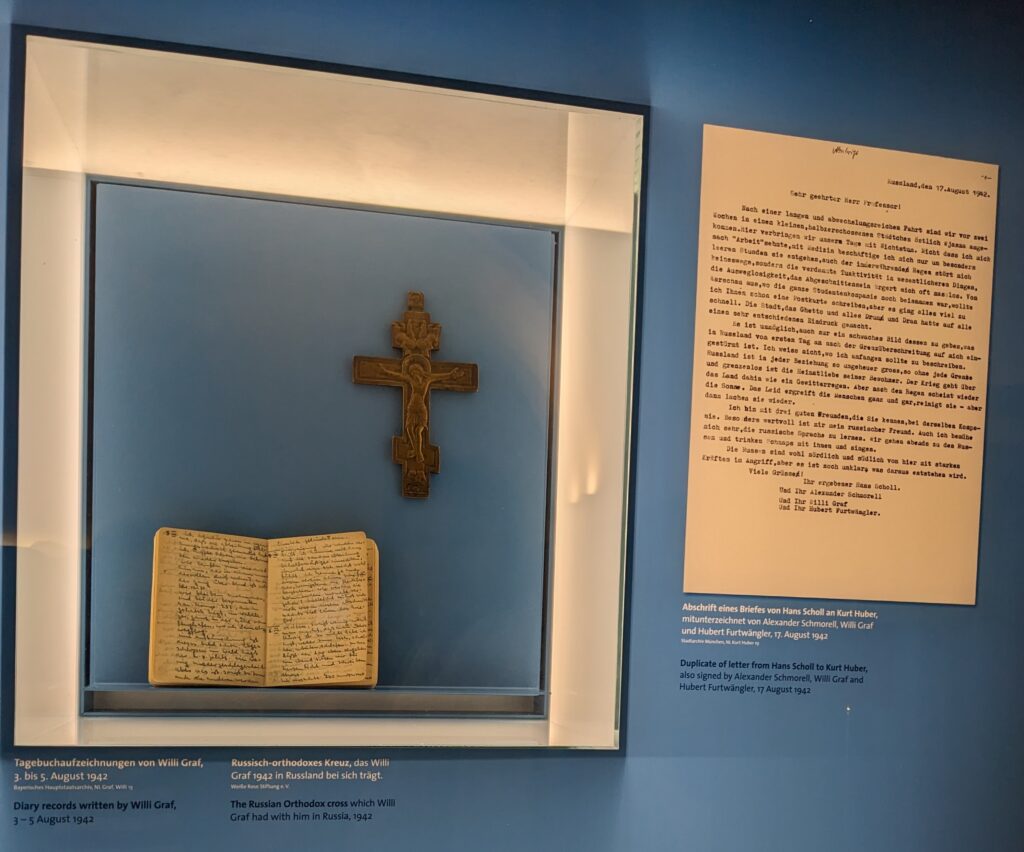

After finishing school Willi Graf had to perform the mandatory Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reich Labour Service). Beginning in winter 1938 he studied medicine in Bonn. In January 1940 he was drafted to the Wehrmacht and had to serve as a medical orderly until April 1942. During this time he witnessed the terrible warfare and the suffering of the civilian population in the Soviet Union which touched him deeply.

In April 1942, Willi continued his studies in Munich. He was assigned to the 2. Studentenkompanie (Second Students’ Company) where he met Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell. They were like-minded, also in their critical attitude towards the National Socialist regime, and became close friends.

From mid July until the end of October 1942 Graf served at the front near Moscow along with Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell and others from the Students’ Company. After their return, Graf actively supported the resistance of the White Rose. He also tried gain supporters among his friends in Cologne, Bonn, Saarbrücken, Freiburg and Ulm.

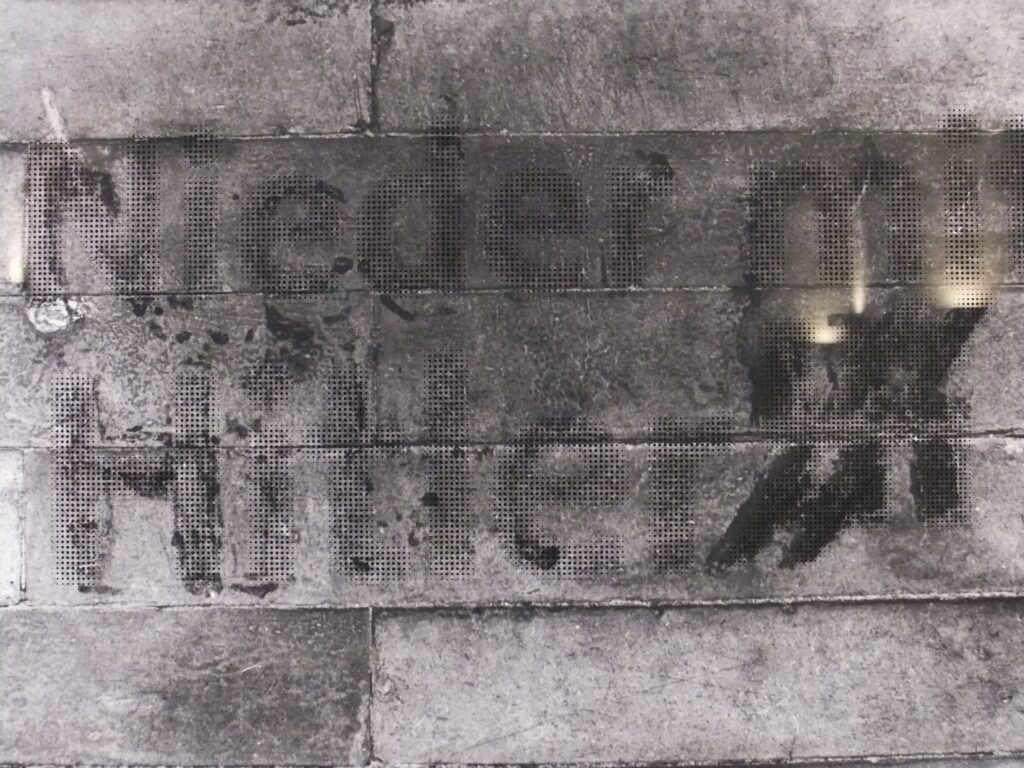

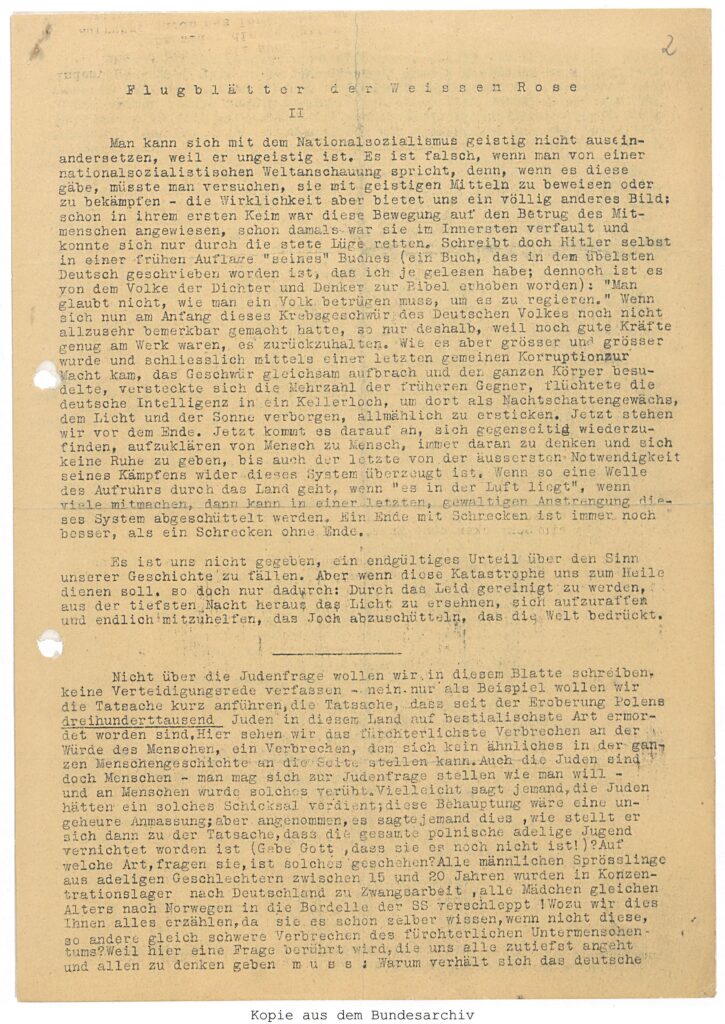

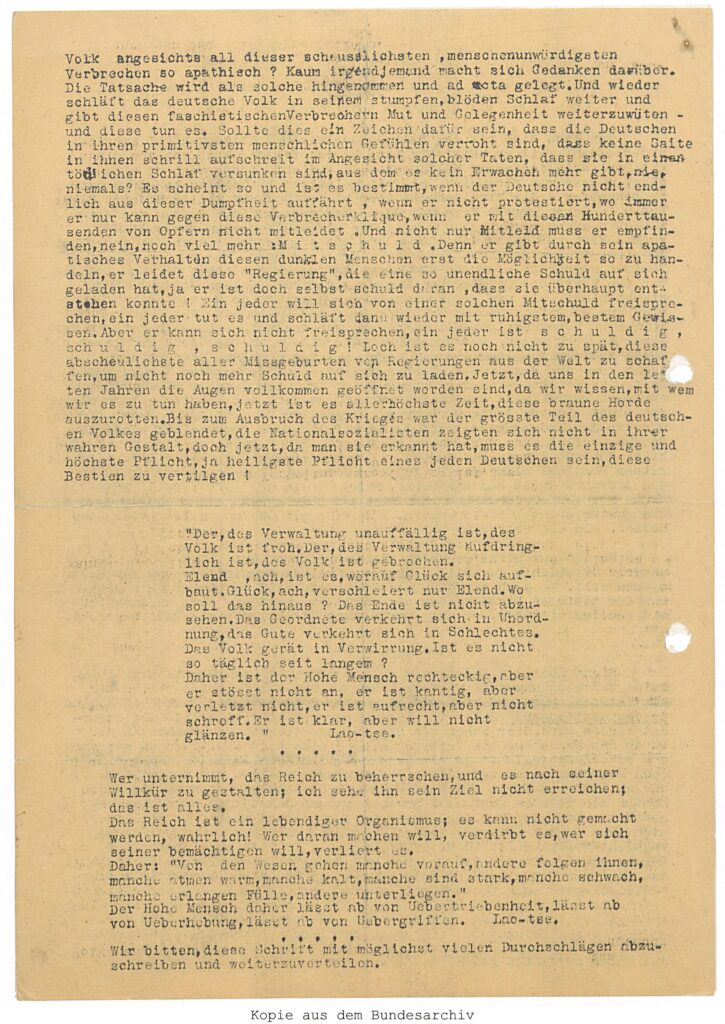

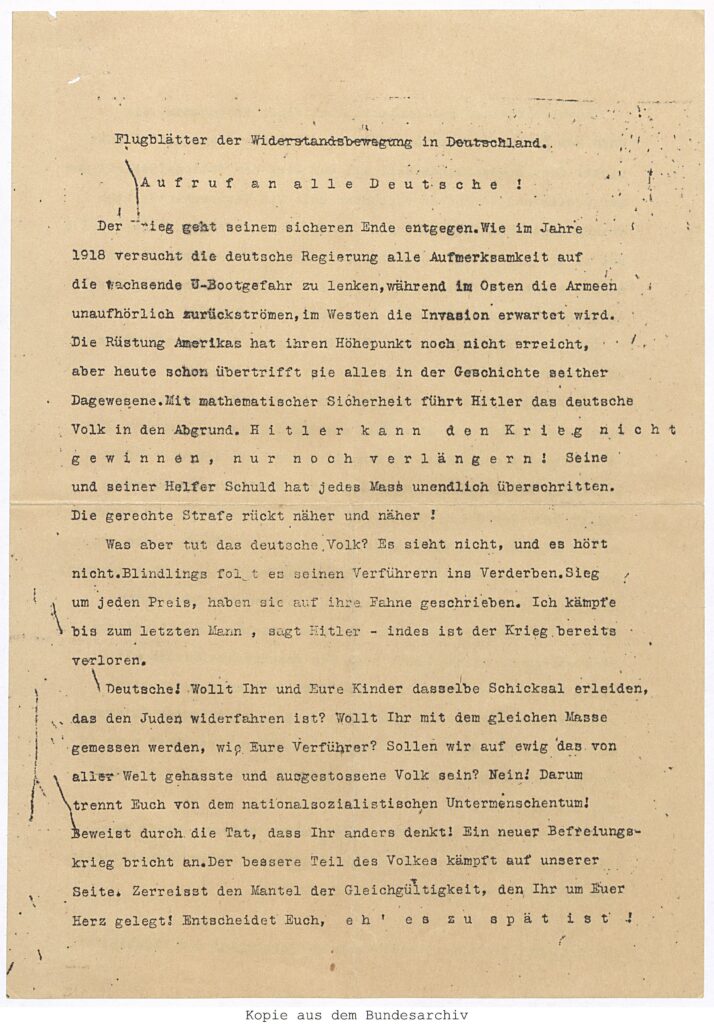

From January 1943 Willi Graf helped to produce and distribute the fifth and sixth leaflet. In February, Willi Graf, Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell wrote “Down with Hitler”, “Hitler Mass Murderer” and “Freedom” on the walls of the university and numerous other buildings in the center of Munich.

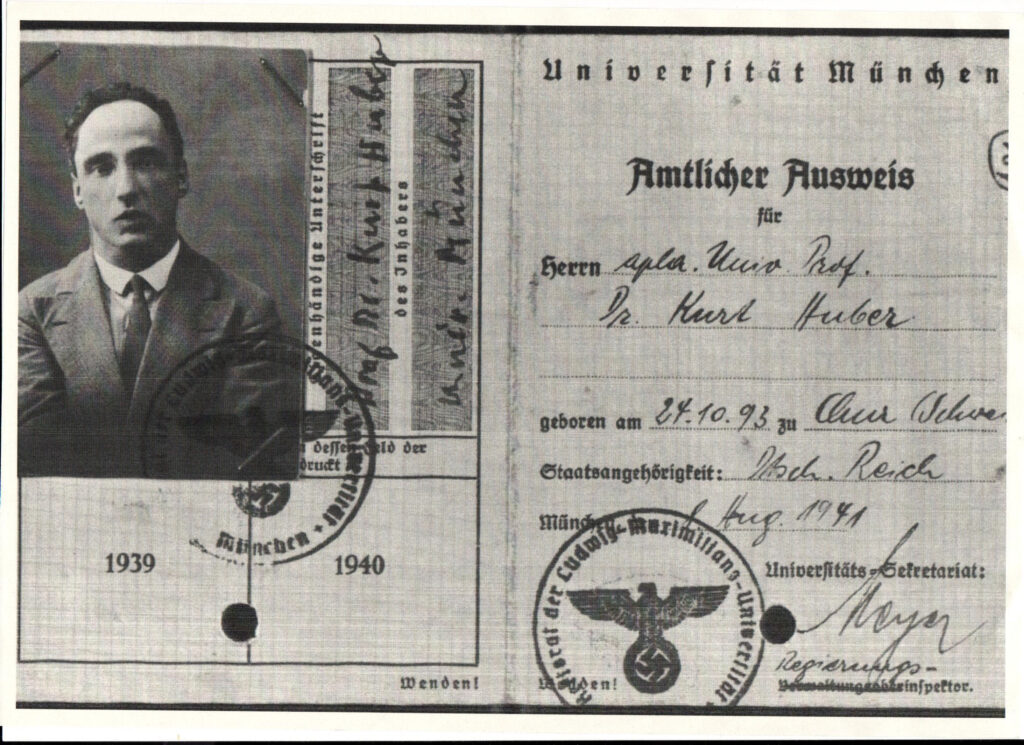

Together with his sister Anneliese Graf he was detained on 18 February 1943, the same day, Hans and Sophie Scholl were arrested. The Volksgerichtshof (People’s Court) sentenced Willi Graf to death on 19 April 1943, along with Alexander Schmorell and Kurt Huber.

Willi Graf was executed 12 October 1943, after seven months on death row and further interrogations.

© Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv

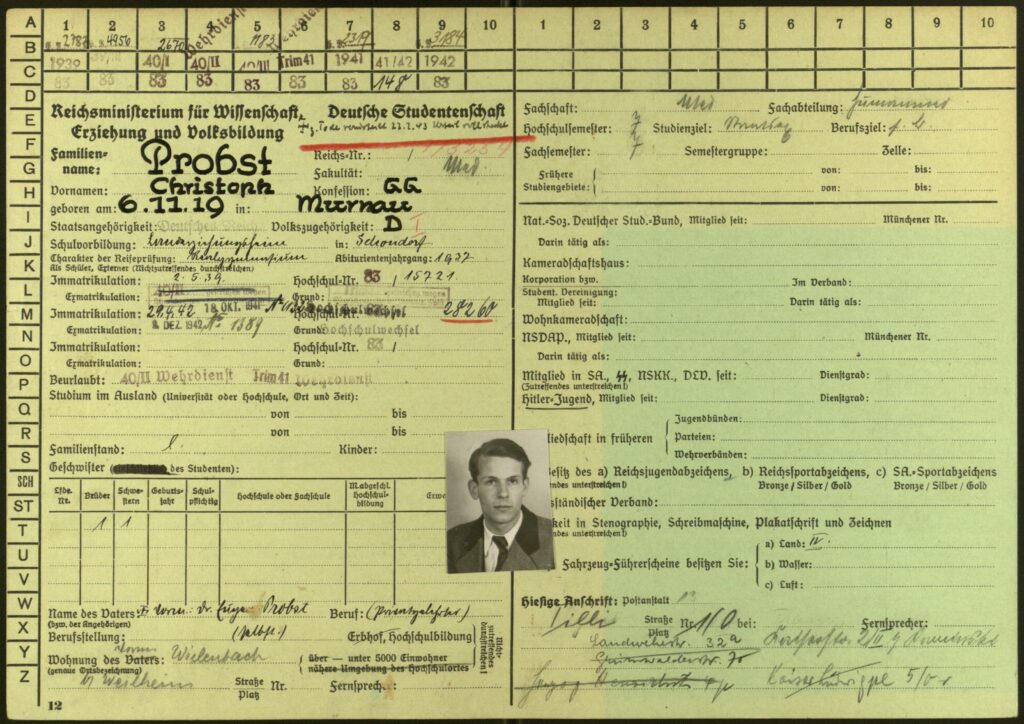

© Bundesarchiv Berlin